Fast, affordable Internet access for all.

News stories highlighting the breadth and depth of the digital divide and its impacts in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic have dominated the headlines in recent months, but a new report emphasizes the degree to which dozens of communities in one Canadian province have struggled with connectivity issues for years. The recently released Nunavut Infrastructure Gap Report [pdf] shows what broadband access looks like for the 35,000 or so mostly Inuit residents of the nation’s youngest province, and what solutions exist for closing the gap for tens of thousands who struggle to get online.

Nunavut is the northernmost of Canada’s provinces, made up of two interlocking geographies: the landmass immediately north of Manitoba and east of the Northwest Territories, and the large collection of islands curled around Baffin Bay to the west of Greenland. It has a population barely 1/20th the size of Wyoming (the U.S.’s smallest by population) despite being the second-largest political subdivision by area in North America, and a population density of just 0.05 persons/square mile.

A Host of Infrastructure Gaps

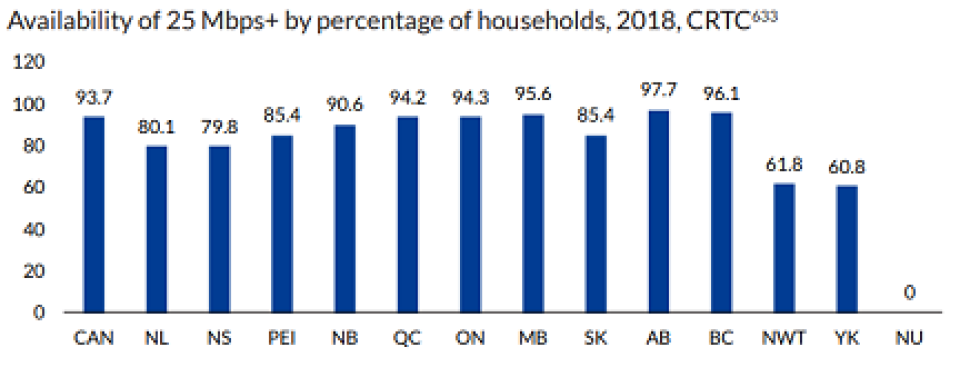

The new report was released by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. (NTI), an “organization that represents the territory’s 33,000 Inuit and their rights.” It looks to quantify existing infrastructure and obstacles in support of the pledge made by the Canadian government in 2019 to close gaps where they exist around the country. The report covers wide range of projects, but broadband access plays a prominent role in the province’s telecommunications infrastructure gap, especially in light of the nation’s goal to achieve universal 50/10 Mbps (Megabits per second) access by 2030.

Its aim, according to NTI President Aluki Kotierk, is “not so much to draw attention on the deplorable state of infrastructure in our communities, as it is to set the premise for a renewed engagement with our partners on fulfilling the aspirations of Inuit.” It outlines several realities faced by those in the region, many of which would be mitigated by affordable, reliable, sufficiently fast Internet access.

For instance:

- A shortage of health care infrastructure and services means that approximately half of the children born to Nunavut Inuit are delivered in Southern hospitals.

- Getting treatment for a serious or chronic illness can mean living away from home (e.g. in Ottawa) for a long stretch of time.

- Nunavut Inuit have limited opportunities to pursue post-secondary education or training in their communities, or even within the territory.

- An enduring lack of Inuktut-based public education means the number of fluent professionals who can work and provide service in the mother tongue of Nunavut Inuit remains limited.

- For Nunavut Inuit with disabilities, a lack of locally available services can mean a heartbreaking choice to leave their community behind altogether to access reliable supports for themselves or their family members.

- For those who enter the federal corrections system, a lack of facilities in the territory mean serving a custodial sentence far from home with little connection to family.

Importantly, it underscores that these “[i]nfrastructure gaps do not exist in silos,” but “intersect and overlap, amplifying the impact of each gap in a combined experience.” The outcome for many Nunavut families is hardship.

No Wireline Broadband as Far as the Eye Can See

All of the above are exacerbated by the complete dearth of wireline broadband networks in the province; none exists in the entirety of Nunavut, making it unique across the whole of Canada. Internet access instead reaches residents’ homes via geostationary satellites which feed fixed and mobile wireless last-mile connections. The vast majority of residents are served by a single provider: Northwestel offers fixed wireless service while Bell Mobility and SSi deliver LTE coverage. However, speed, reliability, and coverage remain sorely lacking while costs place a heavy burden on households trying to get online. As a result, the fastest connections available (15 Mbps) are 85 percent slower than the average connection available (126 Mbps) in the rest of the nation:

The jurisdiction in Canada that might benefit the most from effective online technologies has the worst overall Internet services in the country.

Data caps likewise play a large role in increasing costs and widening the digital divide in the province. Most service tiers across providers, the report explains, are capped at 100Gb/month, which is less than half of the average Canadian household usage in 2018. “An Iqaluit household subscribing to what Northwestel calls its ‘heavy user’ package would pay $436 dollars in additional overage fees just to meet the Canadian average of 209 GB,” the report shares. “This would result in a monthly bill of about $570.”

Several projects have been proposed to address the connectivity gap, including a 1050-mile underwater fiber line between Nuuk, Greenland and the Iqaluit and Kimmirut regions that is currently under construction but delayed by the pandemic, a link between Manitoba’s hydroelectric fiber network and the Kivalliq region, and a potential deal to pay Telesat $600 million over ten years for increased capacity, speed, and coverage using its LEO satellite network. In the case of the latter, the report articulates the problem of using a satellite network providing the only connection:

Relying entirely on satellite technology for core telecommunications functions leaves Nunavut at risk of disruption: not just causing individual inconvenience, but rendering territory-wide systems incapable of functioning. On October 6, 2011, a problem with Telesat satellite “Anik F2” resulted in a 16-hour-long outage of communications services. Every community in Nunavut (as well as several in the Northwest Territories and the Yukon) lost cellular service, Internet access, long-distance telephone access, and some television channels. As a result, flights were grounded, [and] ATMs and key banking services were unusable.

Inuit envision a time where, like any other Canadian, we can take for granted that our basic infrastructure needs are met and surpassed. The information gathered in this report is not only valuable and informative, but it can act as a catalyst for our partners to put into action initiatives that will meet our infrastructure needs so that one day, we may, again, thrive and contribute positively to the broader Canadian society.

Community broadband networks are few and far between in our neighbor to the north, but increased efforts recently mean that some places will see faster, more affordable service over the next few years. We’ve written about the efforts of local leaders and stakeholders in Campbell River, British Columbia to build an open access municipal network. A grant from the Internet Society is fueling another project in Ulukhaktok. And Pictou County is beginning construction on an $11 million dollar fiber network which will make use of fixed wireless for some hard-to-reach places in the region.

There’s no doubt that the pandemic has underscored the importance of Internet service, as well as the stark differences between how huge corporations like AT&T have acted and the steps communities have taken.

Read the full Nunavut Infrastructure Gap Report here [pdf], or download it below.

Panorama image of Pond Inlet, Nunavut by Peter Prokosch